Smith Institute developed Adaptive Social Learning (ASL), a decentralised framework that enables independent agents to detect, interpret, and respond collaboratively to emerging risks, without relying on high-bandwidth infrastructure or centralised oversight. It offers decision-makers a practical blueprint for building resilient and responsive digital infrastructure.

The research was managed by Frazer-Nash Consultancy Ltd, on behalf of the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) which is an executive agency of the UK Ministry of Defence. It provides world class expertise and delivering cutting-edge science and technology for the benefit of the nation and its allies.

ADAPTING TO DYNAMIC, DISTRIBUTED THREATS

The Challenge

The rapidity and sophistication of cyber threats risk outpacing conventional solutions. They have the potential to swiftly spread through entire networks, systems and organisations. Single-agent defences struggle with scalability and adaptability, especially in networks that have limited bandwidth, evolving topologies (such as mesh networks or mobile infrastructure), and partial failures.

Organisations need enhanced network and operational resilience that can autonomously react to threats at machine speed to protect what is often a broad, varied, decentralised network. The variety of nodes and bandwidths within a network presents an additional challenge for decision-makers. Traditional cybersecurity approaches are limited by the nodes with the lowest bandwidth, creating weak links that can be exploited by malicious actors. To protect critical organisational infrastructure, decision-makers need cyber defence that can scale across a range of network sizes and operate effectively under bandwidth and resource constraints.

ENABLING REAL-TIME, DECENTRALISED COORDINATION

The Solution

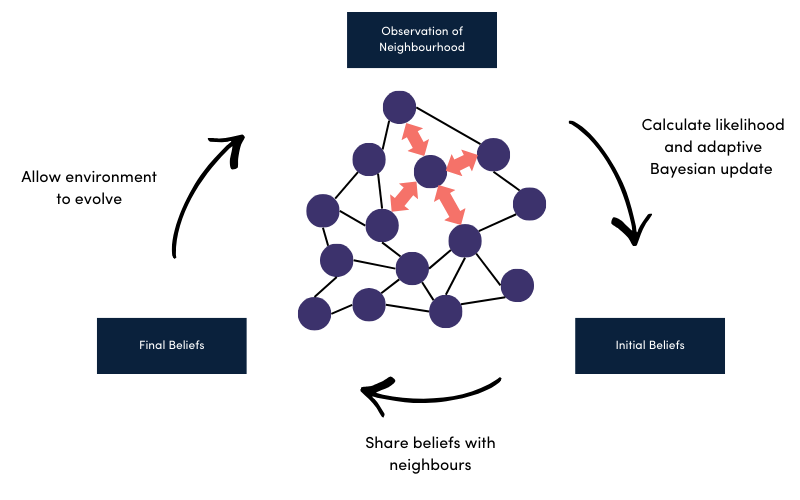

ASL is an agent-based architecture in which each node independently monitors its environment, forms a belief about the system’s state, and shares lightweight updates, typically around 256 bytes, with its neighbours. These updates allow agents to build a distributed understanding of local and global conditions without relying on central control.

Crucially, each agent maintains a built-in scepticism: it evaluates incoming beliefs based on local environmental cues and may choose to trust or discount its neighbours’ inputs. This selective trust mechanism ensures resilience even when some nodes are compromised, enabling coordinated, reliable response across the network.

Figure 1 below illustrates the belief-update cycle, demonstrating how agents collectively build an understanding of system-wide conditions, enabling coordinated action without central control.

If an agent detects unusual traffic patterns suggesting a potential intrusion, it shares this alert with neighbouring nodes. Other agents weigh this information against their own observations, confirming the threat before initiating defensive actions such as isolating affected subnets or activating firewalls. This ensures coordinated and reliable response, even if some nodes provide misleading or corrupted data.

ASL complements human cybersecurity teams, enabling faster, more adaptive decision-making. Its modular design supports deployment across diverse hardware, including low-resource devices. In testing, memory usage was around 3.9 MB per node, with lightweight variants feasible for basic IoT devices and heavier tasks handled by more capable nodes. Rather than being limited by the weakest link, ASL leverages collective strength to support less capable nodes.

The framework was validated in two simulation environments. A proof of concept showed ASL combined with reinforcement learning could defend against attacks. Agents trained in small networks were then deployed into larger, more complex environments, scaling up to 121 nodes without retraining. They retained full functionality and delivered effective defence, demonstrating ASL’s potential for scalable deployment with minimal configuration.

ASL’s decentralised, explainable coordination aligns with key international cyber-resilience priorities, including those set out by the United Nations, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), which highlight the need to build resilience at scale, strengthen critical national infrastructure, and partner with regulators and industry to raise resilience where it matters most. The NCSC’s Annual Review 2025 also highlights the need to be proactive, treating cyber risk as critical to business continuity, reputation, and economic security.

SCALABLE, AUTONOMOUS DEFENCE FOR REAL-WORLD NETWORKS

The Impact

ASL has demonstrated robust, scalable, and efficient performance across a wide range of network configurations. Agents coordinated their actions autonomously while maintaining situational awareness without central oversight. The system proved especially effective in fragmented environments; even under severe network degradation, where up to 62% of connections were removed, agents continued to operate reliably, preserving coordination and defensive capability despite partial disconnection or node compromise.

ASL’s scalability means it can be deployed in networks ranging from a handful of devices to large, complex infrastructures, without the need for retraining or extensive reconfiguration. This flexibility is critical for organisations managing dynamic environments, such as expanding operational networks or responding to dynamic, evolving threats.

Application scenarios include:

- Drone swarms e.g. detecting GPS interference and locally validating signal integrity, enabling autonomous mission control even in contested environments.

- Critical infrastructure maintaining situational awareness and coordinated defence during partial network outages, reducing downtime and operational risk.

- Tactical mesh networks in military or emergency settings, where communication is degraded or intermittent, ensuring robust defence and coordination.

- Industry 4.0 sensors identifying process faults without relying on upstream data aggregation, supporting resilient manufacturing operations.

Figure 2 shows a potential real-world use case for ASL: a drone swarm detecting GPS interference. Drones could communicate with neighbours to detect anomalies in GPS positions. Beliefs would be shared locally, and once a threshold of certainty is reached, mission control would be notified. The red box indicates the interference area, while connecting lines and colour-coded drones show the flow of information and decision-making.

For decision-makers who are accountable for safe, compliant, and scalable AI deployment, ASL demonstrates how autonomous, distributed defence can unlock trustworthy, operational resilience and strategic advantage in the face of evolving threats.

This work shows that Adaptive Social Learning is not just a theoretical approach, but a practical model for introducing autonomy into cyber defence without sacrificing control, assurance, or consistency. The results demonstrate that distributed agents can make aligned decisions, reason under uncertainty, and adapt at machine speed, even in complex and degraded environments. This establishes ASL as a credible technical foundation for future cyber-resilience capability.

Crucially, ASL shows how decentralised defence can remain structured, explainable, and policy relevant. It provides a clear pathway for developing autonomous cyber capabilities that are auditable and aligned with strategic intent, helping organisations move beyond centralised architectures that struggle to scale or respond in real time.

Potential future work avenues could include ASL’s integration within existing planning frameworks, system architectures, and assurance regimes. This will allow autonomous defence capabilities to evolve in a controlled and transparent way, supporting informed capability development as operational environments continue to grow in scale and complexity